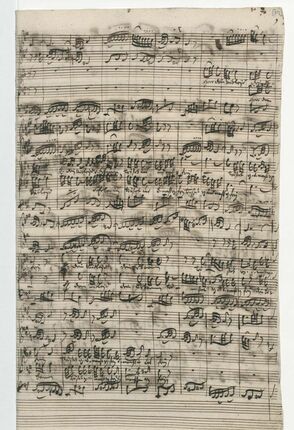

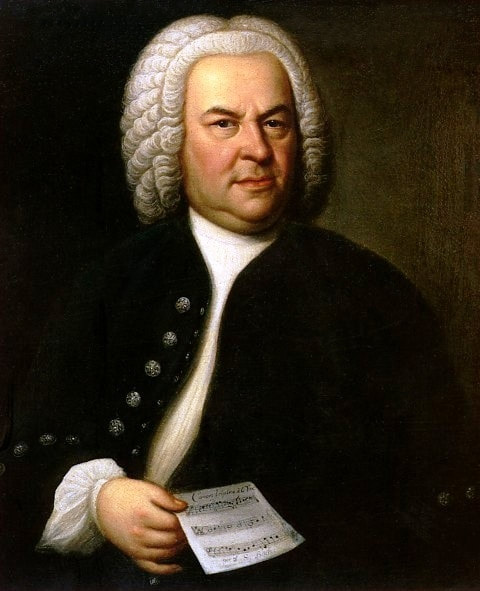

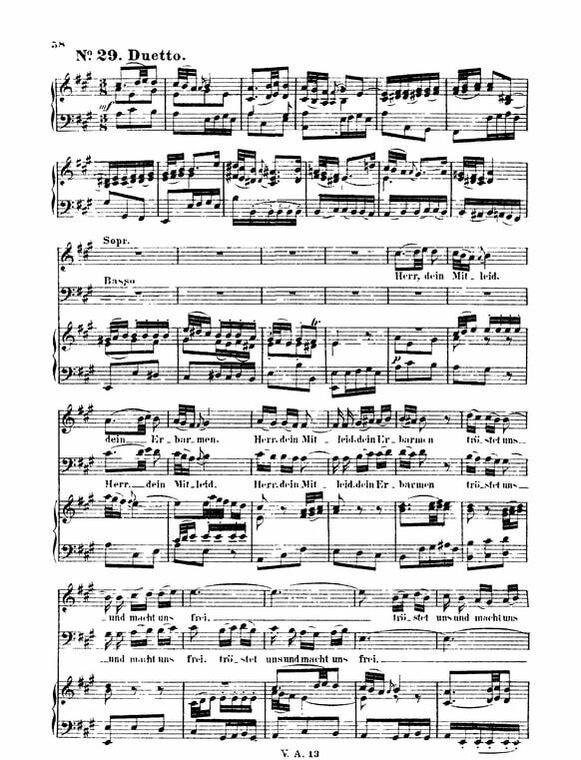

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to hear one of my favorite pieces of music, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Weihnachtsoratorium), BWV 248. This perennial favorite – the equivalent in the German-speaking world of Handel’s Messiah – is a large scale, structurally exquisite, major work for soloists, chorus and orchestra. It consists of six separate cantatas (a liturgical work consisting of hymns, Gospel passages, and reflective poetry in the form of arias for use in the Lutheran Church’s worship setting), each laid out according to the days of the season of Christmas: the first day of the Nativity, second day, third day, New Year’s Day, the Circumcision/Naming of Jesus and finally the Epiphany or Baptism of Jesus. Composed for the Christmas season of 1734, Bach reworked many sections from his previously written (and discarded) cantatas into this tour de force masterpiece of the Baroque era. His skill and his technical mastery were at the height of their power, and it shows throughout the two-and-a-half-hour long excursion into the heart of the Christmas story and message. I had fallen in love with the Christmas Oratorio when I was a music student in college, on account of its thrilling choral numbers, stirring arias and the readily recognizable Gospel narrative of Jesus’s birth (the wise men, the shepherds, the angels, etc.) that runs throughout its entirety. Among my vast collection of CDs it is a work that gets guaranteed play time at least once a year, if not more… simply when I am in the mood to listen, not because it is the Christmas season, but because of how likeable and inspiring the music is. For this reason, when I had heard earlier this year that the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Tanglewood Festival Chorus were planning on performing this great work in its entirety, at the start of the Christmas season in early December, I knew I just HAD to take the opportunity to hear it live and enjoy the music I had fallen in love with so many years ago. I invited my mother to attend with me (as a fellow music lover, she has been my “concert buddy” throughout the years) and she readily accepted the invitation. A few sniffles from an early season cold did not deter me from attending and enjoying this music. However, as we entered Boston Symphony Hall and the ushers were handing out program booklets, they were also handing out a supplemental booklet that had the English translation of the entire German text. She handed one to my mother. I went to reach out my hand to receive a copy as well -- there was an abrupt change in the usher’s demeanor. “Are you two together?” she asked. “I’m sorry, only one per party. The print run was limited and we don’t have enough for everybody.” “Uh-oh,” I thought. “Will there be supertitles over the stage?” I asked cautiously, referring to a common practice at orchestral halls where vocal works with foreign language texts are to be performed. But by that time it was too late. We had already been “ushered” in to the hall and she had already begun explaining the situation to the next patrons. When we took our seats, I quickly glanced above the stage to look for a small projection screen. There was none. Gulp. In my mind, I quickly reviewed my knowledge of the piece and made an assessment of just how much I would be able to follow, with my limited German language skills, culled mostly from diction classes and studying music scores when I was a music student and from that week-long class trip to the Germanic countries my junior year in high school. Furthermore, I took into consideration the fact that the backbone of the text was formed by the Biblical narrative of Christ’s birth, coupled with the arias (solo numbers) containing relatively short amounts of text repeated frequently and the choral numbers just being so musically magnificent that I wouldn’t care much about the words anyway. It was all in a split second but at once I became very reassured, self-confident even. My mother handed me the text booklet to use. “We can share it back and forth, if you want,” she offered. “No need,” was my cavalier reply. “I should be able to follow most of it,” a little grin forming in the back of mind for being able to say that. I reassured her that it was fine and that she could follow the booklet (good thing I did, because she used it the entire time), and I settled in to concentrate on the glorious music that was about touch my ears and my heart. About a third of the way in, during Part III about the arrival of the Shepherds to the stable, a beautiful number came up, a duet for Soprano and Bass, accompanied by two oboes. As I was listening to the text, I suddenly realized that I could understand what was being sung! Now, prior to this I had been able to understand some of the text due to the factors I mentioned earlier, but that was because of my having had some familiarity with it already. This was the first time during the performance in which I was able to casually understand what was being said. And here are the words that I understood: Herr dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen, tröstet uns und macht uns frei… “Lord, thy compassion, thy mercy, comfort us and make us free.” (For those German language scholars who are reading, please forgive me if my translation is not entirely correct; I am simply offering the translation as I understood it that evening.)  From a 1734 manuscript of Herr dein Mitleid, from the Christmas Oratorio (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (D-B): Mus.ms. Bach P 32) From a 1734 manuscript of Herr dein Mitleid, from the Christmas Oratorio (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (D-B): Mus.ms. Bach P 32) Thus, as the text was being sung repeatedly, as a musician I began to relish the thought of what I had accomplished, but as a priest and a believer I now began to contemplate the words that were being sung. “Lord, your compassion and your mercy comfort us and set us free…” “Compassion and Mercy” To begin to understand the meaning of this sentence in a Theological context, we must first examine the German word “mitleid.” It is a meaningful word that fuses the words “mit” meaning “with” and “leid” meaning “sorrow.” Thus, an accurate translation would be “to feel sorrow with,” or “to suffer along with.” This corresponds with the English word of Latin origin “compassion,” which could readily be translated to mean the same thing. I would like to emphasize here that the compassion or co-suffering of our Lord is not an abstract emotion or merely a sense of empathy (although that, I believe, is present as well), but rather a true physical suffering. Just as we human beings go through the rigors and difficulties of life and suffer in our flesh because of sickness, disease and persecution, our Lord Jesus Christ as a human being suffered through all those difficulties we do – and in his case, even more so, since in his earthly life he met such a brutal and tortuous end. When speaking about Jesus’s perfection in the role of “High Priest” of God’s Temple, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews refers precisely to this concept, when he writes, “Therefore he had to become like his brothers and sisters in every respect, so that he might be a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God… Because he himself was tested by what he suffered, he is able to help those who are being tested.” (Hebrews 2:17-18) So, Jesus’s compassion is not theoretical, like anyone of us may reach out to a suffering brother or sister and say, “I feel sorry for you,” or even take compassionate actions to try to alleviate his or her suffering. His is the actual kind of compassion, because he personally experiences the same suffering we do. The next word we need to take a look at is “Erbarmen,” which is the German language correspondent of the Greek word elyon, or voghormootyoon in Armenian. This is the word that describes the kind of “loving kindness” that God shows to his people. In times past, it was translated as “mercy,” but it could be argued that the meaning of that word has changed significantly since the time when the Bible was first translated into English. In our day, the term “mercy” conjures up an image of a petulant, inconvenienced bully deciding at his or her whim the fate of an unfortunate inferior. The “mercy” of God as described in the Bible is quite different, however. It is understood to be the very goodness and Fatherly love that God contains in his nature, and that has been shown lovingly toward mankind since time immemorial… the same loving kindness Jesus himself embodied and emulated throughout his earthly life, which of course culminated in his ultimate sacrifice on the cross. This loving kindness was evident in all of his personal interactions that we read about in the Gospel. The entreaty “Der voghormya” (or Lord, be kind to us) epitomizes this perpetual quest for God’s goodness in our lives. It is used profusely throughout the Old and New Testaments, as well as in the liturgical prayers and hymns of our Church. By saying “Der voghormya” or “Lord, have mercy,” we are not begging or groveling, rather we are humbly admitting, “Lord, show us your loving kindness… Be good to us, because we sure need it!” It may not be evident at first, but there is a connection between the two – compassion and loving kindness. Compassion must be present in order for loving “elyon” to take place. Recall that when the crowds were following Jesus, the Gospels record that he had compassion on them and then started healing them and performing miracles In the Gospel of Matthew 14:13-21, we see a prime example of this, wherein upon seeing the crowds – even though he himself was still suffering from the devastating news that John the Baptist had been beheaded – he had compassion on them and began healing them from their illnesses; then he fed a crowd of more than 5,000 people with just five loaves of bread and two fish! Compassion and loving kindness in action. Here, we would be wise to ask the first of two question: what do these two concepts, compassion and loving kindness have to do with Christmas, or more specifically the birth of Christ? Of course, with a broad perspective, we understand the compassion and loving kindness of Jesus to be evident in the life that he lived and the works he did. Taken as whole, one could say that entire course of his life, as charted in the Gospels, he was dedicated to this two-fold work of compassion and showing the loving kindness of God the Father. Jesus Christ did not come into the world simply to “find his way,” or anything else. Compelled by his compassion toward mankind, the Son was sent from the Father in order to save the world and show his loving kindness. He came with a certain mission, and in order to fulfill that mission, he accomplished a certain set of acts that we recognize as necessary elements of this saving mission. In Theological terms, we refer to the entirety of these acts as the “economy” of salvation. Traditionally understood, these encompass primarily his betrayal, his passion, his crucifixion, his resurrection, his ascension and his second coming. How then, you ask, do we understand the incarnation and the birth of Christ in terms of his suffering? After all, from the Gospel narrative it doesn’t seem like there was anything perilous occurring. Furthermore, why would we be contemplating suffering and compassion during the joyful season of Christmas anyway? Aren’t those things supposed to be for Holy Week and the Easter Season? Shouldn’t we be singing about “glad tidings” and “peace on earth” and so forth?

But we must also remember that part of this saving economy was also his incarnation, his birth, his baptism, his presentation to the Temple and his earthly ministry of preaching, teaching, healing and performing miracles. Therefore, while it doesn’t seem obvious at first, these elements of Christ’s economy of salvation that encompass the beginning of his human life are an integral part of its entirety. Our Church Fathers pointed out in many ways that Jesus’s incarnation itself was an act of great compassion. That the all-powerful, all-knowing God of all Creation, whose glory is uncontainable, would undertake to be confined in the womb, be born as a tiny child in the most modest of circumstances was, in their eyes the ultimate act of compassion and loving kindness toward the human race. The incarnation and birth – as much as the passion and crucifixion – of our Lord were seen as acts of suffering and temptation inasmuch as the unconfined God would be gracious enough to be placed within the confines of human flesh, if it meant saving his people from their sins (which is what the word “Jesus” means in its Hebrew definition). In this act also there was seen an infinite measure of God’s love for and care toward humankind. In this very humbling and sacrificial act one could sufficiently see the love and compassion of God in heaven being poured out amongst the peoples of the earth, a beautiful reminder that all of the trials and passions of Jesus’s earthly life were not in vain, neither did he lose his life in vain (we are reminded of this every Easter Sunday), and that there is true power in God’s being moved to suffer for us and show his goodness to us. Now, that Jesus Christ suffered in his flesh is no matter of speculation or philosophical contemplation – it is historical fact and a necessary reality if we are to accept him as “perfect God and perfect Man.” If he truly was perfect in his humanity, as we Orthodox claim, then he would have experienced the whole gamut of passions and sufferings that life as a human being promises. (That he experienced them without sinning in their wake is another subject for a different message.) So now we must ask the second and final question: How do the compassion and loving kindness of Christ, shown in his incarnation, birth and suffering in general, comfort us and set us free? I believe that these two – comfort and liberation – are the natural outcome of having a God who suffers with us and shows us infinite amounts of kindness and love. As far as comfort, in the face of disaster and personal tragedy, we are comforted to know that God is with us in that he himself suffered and knew much tragedy and adversity. The word “comfort,” or mûkhitarootyoon in Armenian, appears numerous times in both the Old and New Testaments. It is part of who God is and what he does. He comforts those in affliction, he speaks comfort to his people, he sends “the Comforter, the Holy Spirit,” to teach us and remind us of his Word. (John 14:25) As Armenian Christians, throughout many centuries of persecution and Genocide in our homeland, the consolation of God, which received through our Armenian Apostolic Holy Church, kept the Armenian spirit alive and allowed us to continue on as a people. This was all because our ancestors knew that whatever cross they had to bear, whatever height of Golgotha they had to traverse in pain and agony, our Lord Jesus Christ had done it with them and therefore was a source of great comfort to them in their most difficult hours. Lastly, to say that God’s compassion and loving kindness “set us free” is first and foremost to acknowledge that we are in captivity. This may seem far-fetched, yet we see around us every day countless examples of men and women being enslaved to such treacherous sins as worship of self, addictions, disregard for authority, disrespect for family members, sexual sins, slander, dishonesty, idolatry, worship of material wealth and perhaps the most grievous of sins: self-delusion. Delusion that we are own creator, delusion that we are our own redeemer, delusion that we can do anything we want without being harmed – delusion that we are God. If we are not careful, this very same self-delusion can lead to a delusional and erroneous understanding of that freedom that has been given to us through Jesus’s compassion and loving kindness. We often have a hard time coming to grips with the fact that we are in captivity, especially as we mature spiritually and our enslavement to sin and our own sinfulness begins to become more evident. (Read Romans 6:16-19 for Saint Paul’s take on this). Often, it seems as though when we finally do turn to our Lord to set us free, we become even more restricted than when we were “slaves to sin!” We have to go to Divine Liturgy, read the Bible, pray every day, confess our sins, live in righteousness, care about others, obey the law and try to be good in God’s sight at all times (which is virtually impossible). Yet in Christ we come to understand that true freedom is in what he offers us – salvation, holiness and eternal life – and not in anything else we can conjure up by working on our own. Through his compassion and loving kindness he has placed us in his good graces (“under grace” to use the biblical terminology). What we must realize is that those things mentioned above are what we do to stay in the good graces of the one who set us free in the first place, because we acknowledge that is is the best possible place to be! When my youngest son gets frustrated because he didn’t get his way, sometimes he slumps his shoulders, puts his face down and says in a fit of frustration, “I’m going to go and do whatever I want! Humph.” To him, this is what freedom looks like. In his mind, he thinks he will finally be freed from the oppressive overreach of authority and be at liberty go wherever he pleases and do whatever he pleases. What he doesn’t realize (especially at that tender age) is that he would also be fleeing the care and kindness of a loving father, who in ways that he cannot yet begin to fathom, has sacrificed for him and suffered along with him, and without whose care for even a day he would have great difficulty surviving in this world. We’ve all been there, haven’t we? Shrugging our proverbial shoulders at our heavenly Father, we ask things like, “Why do I have to apologize first?” “Why am I responsible for doing this or that thing for church?,” “why do I have to give up that sinful habit if I enjoy doing it?” and so on. Much like the example of my son, what we must realize is that our freedom – or more specifically, our intelligent perception of it – should not be used to flee from our responsibilities and actions as newly freed believers, but to come into and remain in the presence of the one who set us free, and not to flee from him altogether. The latter would not be called freedom; this is called being “lost.” There is a big difference between being “free” and being “lost,” although there may be a thin line separating the two with a lot of gray area surrounding it. Sadly, many people in this world mistake being “lost” for being “free.” A sheep may stray from its shepherd and believe it is free, but that sheep can only stray so far before it finds itself in great peril of being lost forever! So too, we must be careful that as Armenian Apostolic Christians our attitudes toward our freedom in Christ wouldn’t result in our being lost altogether and falling out of his good graces. A person who is truly free in the knowledge of Christ remains in the service of Christ, knowing that he or she has the best chance of being nurtured, guided and safely led to the best place for that person to be in his/her life. Freedom is not in doing whatever we want (as my son sometimes concludes), but in our being made wise enough to know our boundaries, understand our limitations and the endless amount of support and power we have in God’s loving kindness, in the faith which he laid out for us in the families, communities and roles he places us in. I pray that during this holy season of our Lord’s Nativity and Theophany you would more and more come to the knowledge that his compassion for mankind and the infinite loving-kindness that he showed through his incarnation, death and resurrection can give you great comfort from the sorrow of your sins and set you free from captivity to evil and death. Քրիստոս ծնաւ եւ յայտնեցաւ: Օրհնեալ է յայտնութիւնն Քրիստոսի: Christ is born and revealed! Blessed is the revelation of Christ. Prayerfully, Fr. Stephan Baljian, Pastor Holy Nativity & Theophany 2019

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

Location |

SEARCH

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed